Imaging Pearls ❯ Kidney ❯ Hematuria

|

-- OR -- |

|

- Methods The latest available ACR Appropriateness Recommendations, AUA guidelines, and CUA guidelines were reviewed. AUA and CUA guidelines imaging recommendations by variants and level of appropriateness were converted to match the style of ACR. Imaging recommendations including modality, anatomy, and requirement for contrast were recorded.

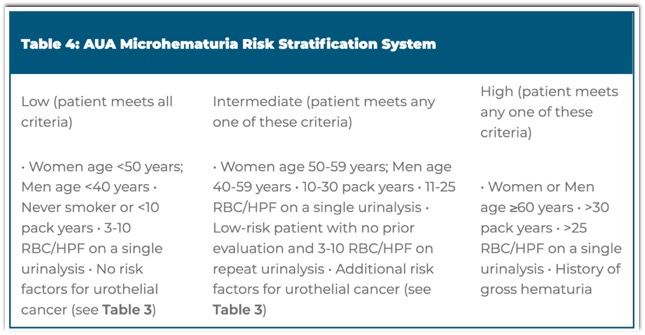

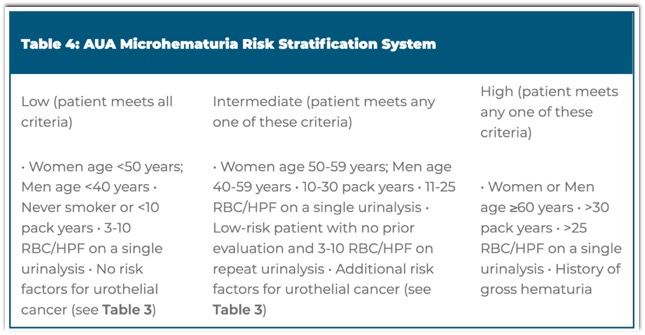

Results Clinical variants included microhematuria without risk factors, microhematuria with risk factors, gross hematuria, and microhematuria during pregnancy. CUA recommends ultrasound kidneys as the first-line imaging study in the first 3 variants; pregnancy is not explicitly addressed. For hematuria without risk factors, ACR does not routinely recommend imaging, while AUA recommends shared decision-making to decide repeat urinalysis versus cystoscopy with ultrasound kidneys. For hematuria with risk factors and gross hematuria, ACR recommends CT urography; MR urography can also be considered in gross hematuria. AUA further stratifies intermediate- and high-risk patients, for which ultrasound kidneys and CT urography are recommended, respectively. For pregnancy, ACR and AUA both recommend ultrasound kidneys, though AUA additionally recommends consideration of CT or MR urography after delivery.

Discrepant guidelines in the evaluation of hematuria

Terrell A. Brown · Justin R. Tse

Abdominal Radiology (2024) 49:202–208 - Conclusion There is no universally agreed upon algorithm for diagnostic evaluation. Discrepancies centered on the role of upper tract imaging with ultrasound versus CT. Prospective studies and/or repeat simulation studies that apply newly updated guidelines are needed to further clarify the role of imaging, particularly for patients with microhematuria with noand intermediate risk factors.

Discrepant guidelines in the evaluation of hematuria

Terrell A. Brown · Justin R. Tse

Abdominal Radiology (2024) 49:202–208 - “In conclusion, ACR and urologic societies have discrepant guidelines on the evaluation of hematuria, which may lead to disparate care. Prospective studies and/or repeat simulation studies that apply newly updated guidelines are needed to further clarify the role of imaging, particularly for patients with microhematuria with no and intermediate risk factors.”

Discrepant guidelines in the evaluation of hematuria

Terrell A. Brown · Justin R. Tse

Abdominal Radiology (2024) 49:202–208

- “Spontaneous renal hemorrhage (SRH) or hematoma is an intraparenchymal renal hemorrhage of unknown origin in a patient without trauma or anticoagulation . SRH is most commonly related to occult vascular renal tumors (angiomyolipoma or renal cell carcinoma), vasculitides (polyarteritis nodosa), or vascular malformations. A few cases are idiopathic or have been attributed to infection, uncontrolled hypertension, ruptured hemorrhagic cysts, or erosion from large renal stones.”

Spontaneous Renal Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Clinical Protocol

Olivia Antonescu et al.

Cureus 13(6): e15547. doi:10.7759/cureus.15547 - "Patients with SRH will classically present with Lenk’s triad of flank pain, tenderness, and “symptoms of blood loss,” including generalized fatigue, tachycardia, dizziness, and hypotension depending on the volume of blood loss. However, it can mimic many acute abdominal pathologies. As such, SRH is usually discovered incidentally on ultrasound or contrast-enhanced abdominal CT. Abdominal CTA however is the preferred imaging modality for definitive diagnosis and preprocedural planning. Laboratory findings often include anemia and hematuria.”

Spontaneous Renal Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Clinical Protocol

Olivia Antonescu et al.

Cureus 13(6): e15547. doi:10.7759/cureus.15547

- ”At the same time, practice-pattern assessments have demonstrated significant deficiencies in the evaluation of patients presenting with hematuria. For example, one study found that less than 50% of patients with hematuria diagnosed in a primary care setting were subsequently referred for urologic evaluation. Furthermore, performance of both cystoscopy and imaging occurs in less than 20% of patients in most series, and varies to some degree by sex and race.The underuse of cystoscopy, and the tendency to rely solely on imaging for evaluation, is particularly concerning since the vast majority of cancers diagnosed among persons with hematuria are bladder cancers, optimally detected with cystoscopy.”

Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU Guideline

Daniel A. Barocas et al.

J Urol 2020 Oct;204(4):778-786. - Diagnosis and Definition of Microhematuria (MH)

Clinicians should define MH as >3 red blood cells per high-power field (RBC/HPF) on microscopic evaluation of a single, properly collected urine specimen. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

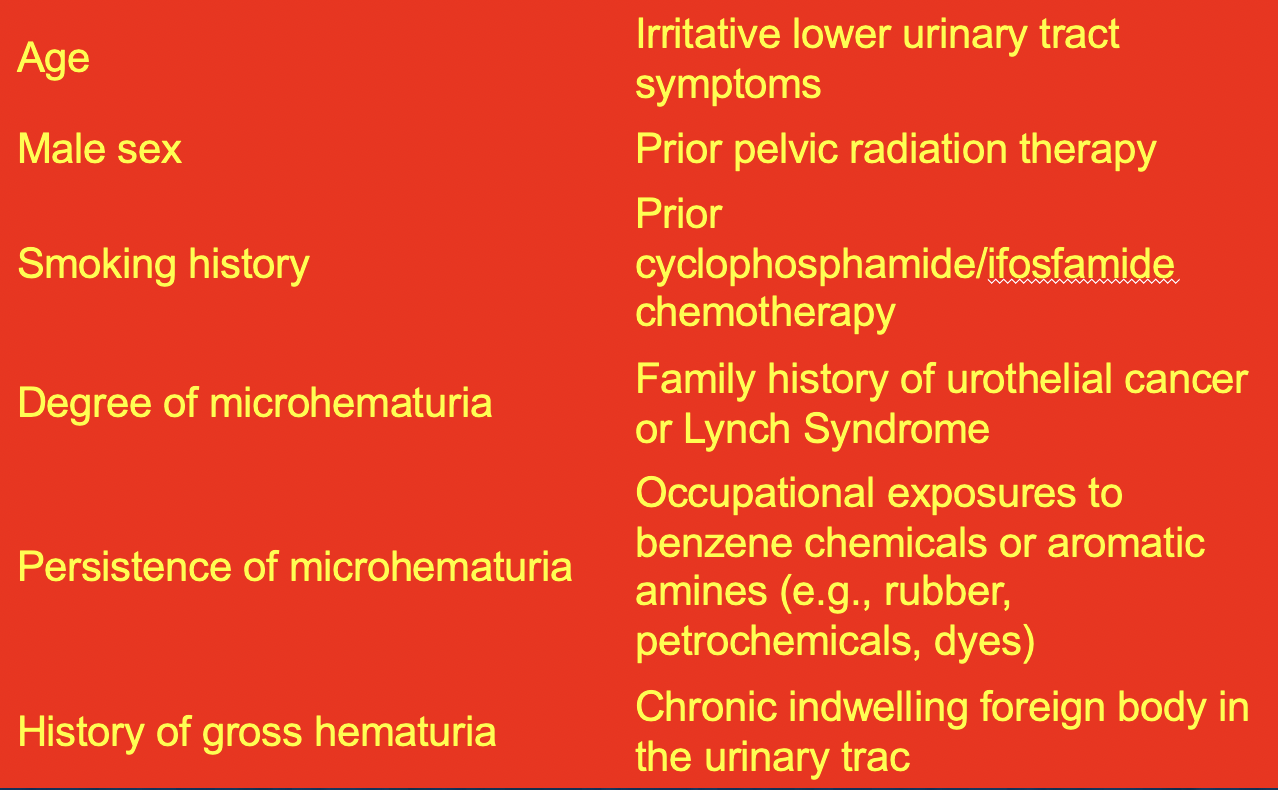

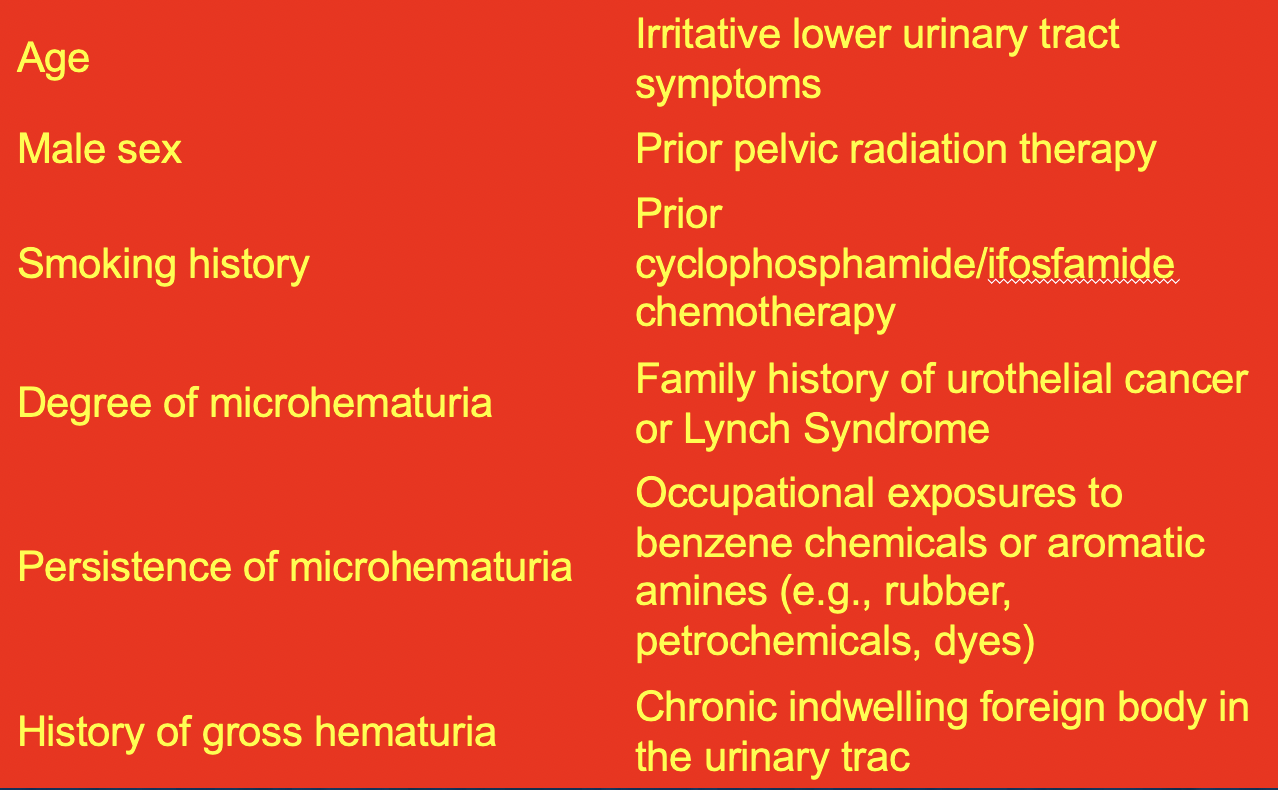

Clinicians should not define MH by positive dipstick testing alone. A positive urine dipstick test (trace blood or greater) should prompt formal microscopic evaluation of the urine. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C) - Risk Factors Included in AUA Microhematuria Risk Stratification System

- AUA Microhematuria Risk Stratification System

- High Risk and Hematuria

Clinicians should perform cystoscopy and axial upper tract imaging in patients with MH categorized as high-risk for malignancy. (Strong Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C) Options for Upper Tract Imaging in High-Risk Patients:

- a. If there are no contraindications to its use, clinicians should perform multiphasic CT urography (including imaging of the urothelium). (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- b. If there are contraindications to multiphasic CT urography, clinicians may utilize MR urography. (Moderate Recommendation; Evidence Level: Grade C)

- c. If there are contraindications to multiphasic CT urography and MR urography, clinicians may utilize retrograde pyelography in conjunction with non-contrast axial imaging or renal ultrasound. (Expert Opinion) - The very limited diagnostic yield of repeated evaluations noted to date from studies of patients followed after a negative hematuria evaluation must be recognized. However, the Panel recognizes that select patients may benefit from and/or request follow-up after a negative hematuria evaluation, or after a negative follow-up UA in a low-risk patient who has not been evaluated. A repeat UA represents an initial, non-invasive modality for continued monitoring. Patients with a negative follow-up UA may be discharged from further hematuria evaluation given the very low risk of malignancy, while patients with persistent MH merit shared decision-making regarding next steps in care. Importantly, changes in a patient’s clinical status, particularly the development of gross hematuria, should prompt clinical review.

Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU Guideline

Daniel A. Barocas et al.

J Urol 2020 Oct;204(4):778-786.

- Perirenal Hematoma: Etiologies Beyond Trauma

• Bleeding is most commonly caused by renal tumours, especially angiomyolipomas.

• Other known causes are long-term haemodialysis, arteriosclerosis or arteritis.

• anticoagulation medication or bleeding diathesis are also causes - “The most common cause of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage is renal neoplasm and approximately 50% of such neoplasms are malignant. CT is the method of choice for evaluation of perirenal hemorrhage, although its sensitivity for detection of underlying etiology is only moderate.”

Etiology of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Zhang JQ1, Fielding JR, Zou KH. J Urol. 2002 Apr;167(4):1593-6.

- “When an acute drop in hemoglobin is noted during initial flank pain evaluation, the primary diagnostic consideration is spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage, the Wunderlich syndrome. The most common underlying cause is a renal mass (both benign and malignant) (62%). However, other con- siderations include vascular diseases (inflammatory and aneurysm) (17%), infection (3%), anticoagulation, and idiopathic causes (13%).”

Acute Urinary Tract Disorders Goel RH et al. Radiol Clin N Am 53 (2015) 1273–1292 - Spontaneous Renal Hemorrhage: Causes

• renal mass (both benign and malignant) (62%)

• vascular diseases (inflammatory and aneurysm) (17%),

• infection (3%),

• anticoagulation

• idiopathic causes (13%).” - “The most common cause of a perirenal hemorrhage is a renal mass. Although less than 1% of renal cell carcinomas bleed, clear cell carcinoma is most prone to hemorrhage given its hypervascularity. Angiomyolipoma (AML), the most common benign renal tumor, is composed of smooth muscle, adipose tissue, and perivascular epithelial cells that form elastin-poor aneurysmal vessels.”

Acute Urinary Tract Disorders Goel RH et al. Radiol Clin N Am 53 (2015) 1273–1292 - “Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), a necrotizing small- medium vessel vasculitis, is the most common cause of bilateral renal hemorrhage.PAN is anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody negative and more common in patients with hepatitis B infection. About 60% of patients with PAN have renal involvement, with intrarenal microaneurysms due to fibrinoid necrosis. CT findings include enlarged kidneys with decreased attenuation, segmental infarcts, and multiple microaneurysms.”

Acute Urinary Tract Disorders Goel RH et al. Radiol Clin N Am 53 (2015) 1273–1292

- What are the risk factors for hematuria?

• Age >40 years

• Male gender

• History of cigarette smoking

• History of chemical exposure (cyclophosphamide, benzenes, aromatic amines)

• History of pelvic radiation

• Irritative voiding symptoms (urgency, frequency, dysuria)

• Prior urologic disease or treatment - Common Causes of Hematuria: Upper Tract

• Urolithiasis

• Pyelonephritis

• Renal cell carcinoma

• Transitional cell carcinoma

• Urinary obstruction

• Benign hematuria - Common Causes of Hematuria: Lower Tract

• Bacterial cystitis (UTI)

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia

• Strenuous exercise ("marathon runner's hematuria")

• Transitional cell carcinoma

• Spurious hematuria (e.g. menses)

• Instrumentation

• Benign hematuria - “Hematuria is defined as the presence of red blood cells in the urine. When visible to the patient, it is termed gross hematuria and is usually alarming to patients. Microscopic hematuria is that detected by the dipstick method or microscopic examination of the urinary sediment.” American Urologic Association

- “Macroscopic haematuria is a commonly seen condition in the emergency department (ED), which has a variety of causes. However, most importantly, macroscopic haematuria has a high diagnostic yield for urological malignancy. 30% of patients presenting with painless haematuria are found to have a malignancy. The majority of these patients can be managed in the outpatient setting.” Management of macroscopic haematuria in the emergency department Hicks D, Li CY Emerg Med J. 2007 Jun; 24(6): 385–390.

- “In men aged >60 years, the positive predictive value of macroscopic haematuria for urological malignancy is 22.1%, and in women of the same age it is 8.3%. In terms of the need for follow‐up investigation, a single episode of haematuria is equally important as recurrent episodes.” Management of macroscopic haematuria in the emergency department Hicks D, Li CY Emerg Med J. 2007 Jun; 24(6): 385–390.

- “Macroscopic haematuria engenders a great deal of anxiety in patients and their relatives. It may be due to a variety of causes, the most serious of which are urological malignancies (most commonly transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, but potentially anywhere along the urinary tract—that is, renal (kidney and renal pelvis), ureteric, prostatic and urethral malignancies). Benign causes include benign prostatic hyperplasia, urinary tract calculi, urinary tract infections (UTIs) and nephrological problems, whereas others include trauma.” Management of macroscopic haematuria in the emergency department Hicks D, Li CY Emerg Med J. 2007 Jun; 24(6): 385–390.

- Differential diagnoses in macroscopic haematuria

• Urinary tract malignancy: kidney, renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, prostate, urethra

• Urinary calculi

• Infections: urinary tract infection, schistosomiasis

• Trauma: penetrating or blunt

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia

• Haemorrhagic cystitis

• Endometriosis

• Nephrological disease: IgA nephropathy, glomerulonephritis

• Postprocedural bleeding—for example, transurethral surgery

• Bleeding disorders, anticoagulation therapy above therapeutic range

• Arteriovenous malformation/angiomyolipoma

• Differential diagnoses in macroscopic haematuria

• Urinary tract malignancy: kidney, renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, prostate, urethra

• Urinary calculi

• Infections: urinary tract infection, schistosomiasis

• Trauma: penetrating or blunt

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia

• Differential diagnoses in macroscopic haematuria

• Haemorrhagic cystitis

• Endometriosis

• Nephrological disease: IgA nephropathy, glomerulonephritis

• Postprocedural bleeding—for example, transurethral surgery

• Bleeding disorders, anticoagulation therapy above therapeutic range

• Arteriovenous malformation/angiomyolipoma

- “OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the yield of repeat CT urography (CTU) in detecting urinary tract malignancies in patients with hematuria.

RESULTS. Initial CTU showed no findings suspicious for malignancy in 103 (70%) of 148 patients; of these, none had malignancy identified on repeat CTU. Among 45 (30%) patients with suspicious initial CTU findings, four malignancies were identified on repeat CTU (8.9%). Three were incidental to the initial suspicious finding; in retrospect, two were present on the initial CTU examination.”

Yield of urinary tract cancer diagnosis with repeat CT urography in patients with hematuria.

Mullen KM et al.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Feb;204(2):318-23. - “OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the yield of repeat CT urography (CTU) in detecting urinary tract malignancies in patients with hematuria.

CONCLUSION. In patients with hematuria, repeat CTU within 3 years is unlikely to show a urinary tract malignancy. These results support currently published guidelines.”

Yield of urinary tract cancer diagnosis with repeat CT urography in patients with hematuria.

Mullen KM et al.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015 Feb;204(2):318-23.

- “ Of patients with hematuria, a source is not identified in 37.3-80.6% of patients.”

In Search of a Consensus: Evaluation of the Patient With hematuria in an Era of Cost Containment

Heller MT, Tublin ME

AJR 2014;202:1179-1186 - “ In 17 screening studies of healthy patients who were found to have asymptomatic microscopic hematuria and underwent subsequent workup, 3762 patients were evaluated and 98 were diagnosed with a urinary tract malignancy, for an overall malignancy rate of 2.6%.”

In Search of a Consensus: Evaluation of the Patient With Hematuria in an Era of Cost Containment

Heller MT, Tublin ME

AJR 2014;202:1179-1186 - “ In patients found to have an asymptomatic microscopic hematuria during an unrelated medical evaluation, 32 studies from initial workups on 9206 patients were reviewed and 368 were found to have a malignancy, yielding an overall malignancy rate of 4%.”

In Search of a Consensus: Evaluation of the Patient With Hematuria in an Era of Cost Containment

Heller MT, Tublin ME

AJR 2014;202:1179-1186 - “ CT Urography provides the most global assessment of the urinary tract and has been reported to identify the source of hematuria in patients triaged for imaging in 33-43% of cases, with an overall sensitivity of 92-100% and specificity of 89-92%.”

In Search of a Consensus: Evaluation of the Patient With Hematuria in an Era of Cost Containment

Heller MT, Tublin ME

AJR 2014;202:1179-1186 - “ The AUA (American Urological Association) endorses CTU as the preferred imaging modality because of its consistently high sensitivity and specificity for detecting lesions of the renal parenchyma and upper urinary tract and its ability to offer optimal and ancillary imaging information.”

In Search of a Consensus: Evaluation of the Patient With Hematuria in an Era of Cost Containment

Heller MT, Tublin ME

AJR 2014;202:1179-1186

- “ In 1856, Wunderlich first described spontaneous renal bleeding with dissection of blood into the subcapsular and/or perinephric spaces.”

Spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: what radiologists need to know

Diaz JR et al.

Emerg Radiol (2011) 18:329-334 - “The major causes of SPH include: renal tumors in 57% to 63% of cases (benign tumors in 24% to 33% of cases and malignant tumors in 30% to 33% of cases), vascular disease in 18% to 26% of cases (polyarteritis nodosa in 12% to 13% of cases), renal infection in 7% to 10% of cases, nephritis, previously undiagnosed hematological conditions, and ruptured cortical cysts. Approximately 7% of cases are idiopathic.”

Spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: what radiologists need to know

Diaz JR et al.

Emerg Radiol (2011) 18:329-334 - “The most common cause of SPH is an underlying renal neoplasm, with angiomyolipoma (AML) being the most common. Fifteen percent of angiomyolipomas present with SPH, and 51% of AMKs larger than 4 cm bleed. The presence of abundant tortuous blood vessels lacking elastic tissue predisposes these tumor to bleed.”

Spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: what radiologists need to know

Diaz JR et al.

Emerg Radiol (2011) 18:329-334 - “ Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the second most common cause of SPH. SPH occurs in 0.3% to 1.4% of cases. Because of its relative frequency, RCC is the most common malignant tumor associated with SPH. Unlike AML, tumor size is not a good indicator of risk for bleeding, as tumors less than 4 cm in diameter are nearly as likely to bleed as larger tumors.”

Spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: what radiologists need to know

Diaz JR et al.

Emerg Radiol (2011) 18:329-334 - “ Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), a systemic panmural necrotizing vasculitis of unknown origin, is the most frequent vascular disease associated with SPH. Less common vascular causes include AV malformations, renal artery rupture, segmental arterial mediolysis, Behcet disease, renal infarction and Wegeners granulomatosis. The kidney may be nvolved in 70-80% of cases of PAN, and SPH is due to aneurysm rupture.”

Spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage: what radiologists need to know

Diaz JR et al.

Emerg Radiol (2011) 18:329-334

- “ The prevalence of clinically important incidental extraurinary findings at MDCT urography performed for hematuria was 6.8%.”

Incidental Clinically Important Extraurinary Findings at MDCT Urography for Hematuria Evaluation: Prevalence in 1209 Consecutive Examinations

Song JH et al.

AJR 2012; 199:618-622 - “ There were 11 (0.9%) examinations with acute findings, of which acute inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary system were the most common. Seventy two (5.9%) examinations revealed 74 nonacute but important findings.”

Incidental Clinically Important Extraurinary Findings at MDCT Urography for Hematuria Evaluation: Prevalence in 1209 Consecutive Examinations

Song JH et al.

AJR 2012; 199:618-622 - “ In 82 of 1209 patients (6.8%) 85 clinically important incidental extraurinary findings were identified. There were 11 (0.9%) examinations with acute findings, of which acute inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and pancreaticobiliary system were the most common. Seventy two (5.9%) examinations revealed 74 nonacute but important findings.”

Incidental Clinically Important Extraurinary Findings at MDCT Urography for Hematuria Evaluation: Prevalence in 1209 Consecutive Examinations

Song JH et al.

AJR 2012; 199:618-622 - “ Lung nodules were the most prevalent, followed by intraabdominal aneurysms and cystic ovarian masses. There were five (1.4%) histologically proven malignant neoplasms.”

Incidental Clinically Important Extraurinary Findings at MDCT Urography for Hematuria Evaluation: Prevalence in 1209 Consecutive Examinations

Song JH et al.

AJR 2012; 199:618-622

Patient Demographics

- 5 Proven Incidental Carcinomas

- 4 cases of bronchogenic carcinoma (3 were stage 1 and 1 had metastatic disease)

- 1 case of lymphoma

- Right Lower Quadrant Pain: Differential Diagnosis

- Genitourinary

- Ovarian torsion

- Ovarian cyst

- Ectopic pregnancy

- PID

- Urolithiasis

- Scrotal inflammation

Imaging of acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain: differential diagnoses beyond appendicitis

Heller MT, Hattoum A

Emerg Radiol (2012) 19:61-73 - “ Urothelial Phase CT urography after the adminisration of a diuretic has the potential to replace conventional dual phase CT urography and become a single phase only technique to help diagnose urothelial tumors in patients at high risk, reducing scanning time and patient radiation exposure.”

Detection of Urothelial Tumors: Comparison of Urothelial Phase with Excretory Phase CT Urography-A Prospective Study

Metser U et al.

Radiology 2012; 264:110-118 - “ Urothelial Phase CT urography after injection of a diuretic has a higher lesion detection rate than excretory phase for both upper and lower urinary tract tumors, which suggests its possible use as a single phase protocol for evaluation of the entire urinary tract in patients at high risk for urothelial tumors.”

Detection of Urothelial Tumors: Comparison of Urothelial Phase with Excretory Phase CT Urography-A Prospective Study

Metser U et al.

Radiology 2012; 264:110-118 - “ The article reviews the life cycle of S haematobium, the modes of its transmission to humans, and the clinical manifestations and imaging features secondary to its infection of the urinary tract and genital organs.”

Genitourinary Schistosomiasis: Life Cycle and Radiologic-Pathologic Findings

Shebel HM et al.

RadioGraphics 2012; 32:1031-1046

- “ The work-up of hematuria should be individualized and risk base. Given the a priori low likelihood of cancer in hematuria, risk categories should be established and imaging algorithms should be tailored to populations at low-risk, medium risk and high risk for developing urothelial cancer.”

Hematuria: A Problem-Based Imaging Algorithm Illustrating the Recent Dutch Guidelines on Hematuria

van der Molen AJ, Hovius MC

AJR 2012; 198:1256-1265 - Risk Factors for Urothelial Neoplasm

- Microscopic vs Macroscopic Hematuria

- Smoking

- Age

- Sex

- Micturition complaints

- Urothelial cancer history

- Chronic UTIs

- Chemical exposure (aromatic amines in industry) - Microscopic vs Macroscopic Hematuria

- In patients with microscopic hematuria neoplasm is uncommon and in he largest study upper urinary tract TCC was found in 0.2%, RCC in 1% and bladder cancer in 3.7% (exact frequency depends on age of population studied)

- In patients with macroscopic hematuria the risk for malignancy is high and can be found in 10-28% of cases overall and in up to 10% of patients younger than 40 years of age (exact frequency depends on age of population studied) - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

- Vascular

- Glomerular

- Uroepithelial

- Miscellaneous

- Hematuria: A Problem-Based Imaging Algorithm Illustrating the Recent Dutch Guidelines on Hematuria

van der Molen AJ, Hovius MC

AJR 2012; 198:1256-1265 - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

1.Vascular

- Arterial embolism or thrombosis

- AVM or arteriovenous fistulae

- Nutcracker syndrome - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

2. Glomerular

- IgA nephropathy

- Alport disease

- Other primary and secondary glomeruloephritides - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

3. Interstitial

- Allergic interstitial nephritis

- Analgetic nephropathy

- Renal cystic disease

- Pyelonephritis

- Renal transplant rejection - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

4. Uroepithelial

- Malignancy (TCC, RCC)

- Heavy physical exercise

- Trauma

- Papillary necrosis

- Cystitis, prostatitis

- Parasitic disease

- Urolithiasis

- Radiation - Frequent Causes of Hematuria

Miscellaneous

- Hypercalciuria

- Hyperuricosuria

- Sickle cell disease - “ CT urography can be used as either a first line diagnostic or as a problem solving test. For first line diagnosis, CT urography should be reserved for patients with a high pretest probability for malignancy, that is, patients 50 years old or older with macroscopic hematuria or the presence of other risk factors.”

Hematuria: A Problem-Based Imaging Algorithm Illustrating the Recent Dutch Guidelines on Hematuria

van der Molen AJ, Hovius MC

AJR 2012; 198:1256-1265 - “Imaging is key in the analysis of hematuria, but it should be realized that CT Urography is a high-dose examination, upper urinary tract urothelial cell cancer is a rare disease, and the risk for malignancy in many patients with microscopic hematuria is relatively low. ”

Hematuria: A Problem-Based Imaging Algorithm Illustrating the Recent Dutch Guidelines on Hematuria

van der Molen AJ, Hovius MC

AJR 2012; 198:1256-1265